🏚️Antifragile (Nassim Nicholas Taleb)

A couple of years ago, I stuck rigidly to a set eating, exercise, and sleeping routine. I ran from change of any sort. It was so bad at one point, I would cook another meal for myself alongside the beautiful meal my parents made for dinner.

I had to stick to my diet.

When I went on vacation, or a random event broke my schedule, it completely threw me off. I had no idea how to deal with disorder. In response, I tried to predict every possible disruption to my day.

This helped a bit. But even so, random events continued to wreak havoc on my routine. I didn't know what to do. I felt frustrated, confused, and hopeless.

Without realizing it, my life system was fragile. I learned why after reading Nassim Talebs's book, Antifragile.

Taleb explains there are three types of systems: fragile, robust, and antifragile. A fragile system falls apart from disorder. A robust system isn't affected by disorder either positively or negatively. And an antifragile system gains from disorder.

Trying to predict and run away from disorder made me fragile. I didn't realize predicting disorder with 100% accuracy was practically impossible.

Luckily, Taleb explains a solution in his book. In his words, "it's far easier to figure out if something is fragile than to predict the occurrences of an event that may harm it."

In other words, it's better to find fragile systems and make them antifragile rather than attempt to predict every disorder that may harm them.

I decided to try make my eating routine antifragile. I was sick and tired of being hurt by randomness. Interestingly, in the process of making my eating routine antifragile, I found ways to make other parts of my life antifragile as well.

In the rest of this blog post, I will discuss how I made my eating routine and some other parts of my life antifragile as well as detail some of the other concepts I found helpful in Taleb's book.

🍇Antifragility Through Fasting

I made my eating routine antifragile by inconsistently implementing fasting into my days.

Fasting means "going without" and usually has to do with eating. Intermittent fasting, the type of fasting I mostly do, involves eating only in an eight hour time block from 11 a.m. to 7 p.m. and not eating for the rest of the day. But I purposefully keep it inconsistent to keep my body on its toes. Sometimes I will eat only one meal or go for a longer, more than a day fast.

When people first hear I intermittent fast, the response is usually the same, "what!? Why? You're starving yourself!? Doesn't that make traveling harder?"

I can confidently say fasting is the easiest and most sustainable method of eating I have ever practiced.

But the main reason I love fasting is because it's antifragile. Say someone steals my lunch box, or I lose my wallet, or there's no healthy food in sight. The solution is simple: I don't eat.

It's so easy it's not even funny. I literally do nothing.

Fasting frees me from the constraint of having to eat on a schedule. Instead of worrying about how I will eat the sacred three meals a day (sometimes with snacks), I can think about literally anything else. If I don’t have an easy way to get dinner—maybe I’m travelling by train—I don’t eat dinner. If I’m not hungry for lunch because I had too big of a dinner the night before, I don’t eat lunch.

Fasting also makes me more in tune with my bodily hunger cues. Hunger is primarily a psychological phenomenon. Physical hunger only comes when our body starts to run low on fat stores.

By regularly fasting, I become better at differentiating when I truly need food from when my body is simply craving something. I get better at avoiding the donuts--with some exceptions of course. When I do submit to cravings or indulgences, I can do so without feeling bad because I can always fast to give my body time to rest and recover.

Biologically, fasting switches my cells into a state of autophagy, a self-recycling mode where they clean themselves of junk.

It also makes me more metabolically flexible. While fasting your body switches primarily to fat as its main form of energy. Then, once you eat, it switches back to glucose.

By inconsistently fasting, intermittent fasting on some days, doing OMAD (One Meal A Day) on others, and sometimes doing prolonged fasts, you train your cells to switch seamlessly back and forth between burning fat and burning sugar for energy.

Finally, fasting helps me make my other routines more antifragile. Going without in my eating habits readies me for going without in other parts of life. It’s helping me fast from digital media, news, and negative social interaction to name a few.

📖Antifragility Through Reading

A second way I have made myself antifragile is through my reading habits. There are two things I'm now doing after learning the concept of antifragility.

First, I blend a bizarre bowl. This is a weird combination of books nobody else has ever read. The disorder of ideas creates novel connections and fosters insight.

For example, I recently read a book called A Little History of Literature by John Sutherland while reading Actionable Gamification by Yu-Kai Chou.

Did these two authors think they would be in conversation with each other? Probably not.

But mixing these authors' books simultaneously has given me some interesting future ideas for blog posts and videos—for instance, a blog post on how to gamify your reading habit.

The second way I create antifragility is through understanding the Lindy Effect. The Lindy Effect states the future life expectancy of something is directly correlated with how long it has been alive.

Time is one of the largest facilitators of disorder. The longer a book has been around, the more antifragile it is, and the more likely it has timeless and insightful ideas.

Because of the Lindy Effect, I now read old books alongside new ones. Books like Marcus Aurelius' Meditations, Seneca's Letters from a Stoic, The Illiad, and the Nicomachean Ethics by Aristotle, to name a few.

✈️Antifragility Through Traveling

The third way I have made myself antifragile is through travel. Traveling made me antifragile for three main reasons:

- I meet new people

- I get immersed in new cultures

- I'm forced to change my routine

For example, I recently finished a trip to London, Sweden, and The Netherlands. On this travel, I met some of the oldest and wisest people I know.

In London, I received wisdom from relatives such as "living a good enough life is the way to be happy" and "relationships are everything." As an eighteen-year-old, I likely wouldn't expose myself to wisdom like this in my personal safety bubble back at University.

In addition, my perspective on life was forever altered by being immersed in cultures different from my own. American culture promotes opportunity, individualism, and following one's passion. But in Sweden, the culture I was exposed to is what I can only describe as more "realistic." Most people don't see themselves as the next Bill Gates or Steve Jobs. Instead, they want to live a "good enough" life.

This made me question my own life ambitions. Why should I be the next great entrepreneur? What sacrifices would being that ambitious have on my relationships and other passions? Is living a good enough life not good enough?

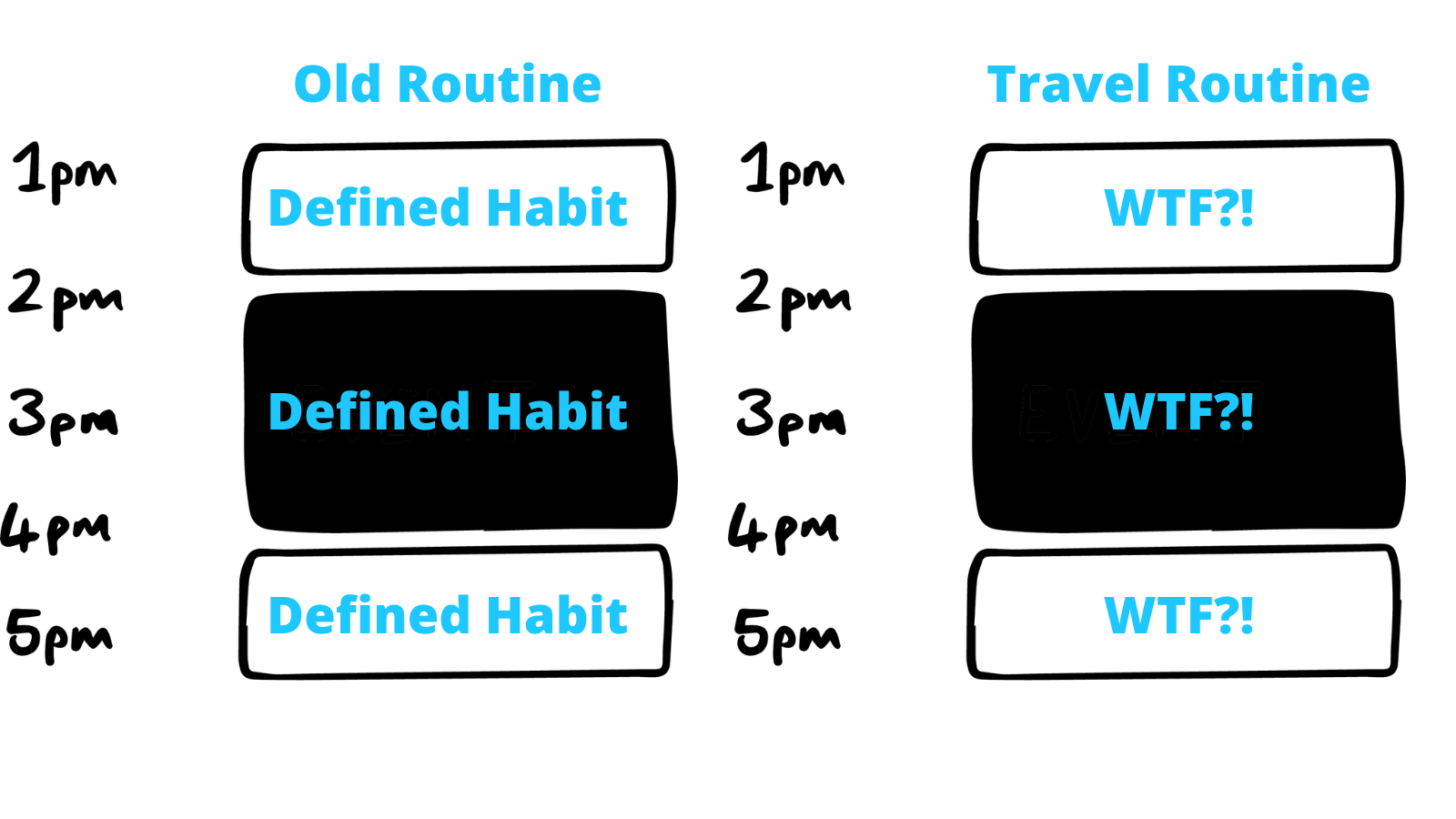

Finally, this traveling adventure forced me to change my routine constantly. I had to switch up my diet, gym timing, sleep schedule, and more. I had to learn to improvise when inevitable disorder came.

I also had to subtract several habits I no longer had time for. For example, I rarely had the time to read for an hour and a half at night nor do a full three hours of writing in the morning. Many days, my relatives would want to do something early in the morning or dinner conversations would be pushed until late at night.

This made me more flexible. I stopped feeling like everything had to be done at the same time and in the same place every time. I started to appreciate simply being among others I loved.

🦢Black Swans

Hopefully, with these three examples, you are starting to understand how beneficial crafting antifragile systems in your life can be.

But we still haven't learned what makes fragile systems so weak against disorder. This will give us an idea for the dangers of ignoring fragility.

The largest problem with fragile systems is they are prone to Black Swans, rare and highly unpredictable outlier events almost impossible to predict.

According to Behavioral Economist Danielle Kahneman, humans are terrible at thinking statistically. We are fantastic at remembering images and their associations but never evolved naturally to memorize or understand numbers. This makes Black Swans the bane of our existence.

Taleb states humans mistakenly believe "absence of evidence is evidence of absence." But as I will now explain, this is not always the case.

Take the global financial crisis of 2008, for example. The financial crisis was caused primarily due to predatory lending targeting low-income house buyers and excessive risk-taking by financial institutions. For a long time, nobody but a select few thought anything was amiss. People said the real estate market was iron clad.

But in 2008, this excessive risk-taking and loaning culminated in a massive price drop in Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS) tied to American real estate and webs of derivatives linked to those MBS. In this case, the real estate system was fragile because it was filled with corrupt bankers. Over time this led to a Black Swan slowly building up and culminating in the crisis.

Black Swans aren't only present in finance. They're everywhere. There is almost certainly one building beneath you right now.

This is why making yourself, and others antifragile is so essential. As said earlier, it's impossible to predict the future with 100% certainty. Instead, you should make yourself antifragile so you can benefit from disorder, all without having to rely on predictions.

➕Addition Through Subtraction

Another enlightening philosophy Taleb details in his book is the concept of Via Negativa: improving systems through subtracting rather than adding.

Humans usually don't see this option because we have an innate tendency to add rather than subtract. I detail this concept thoroughly in my book summary of, Subtract: The Untapped Science of Less, by Leidy Klotz. His studies found humans, whether building, writing, cooking, or scheduling, had an innate tendency to add rather than subtract.

But often, subtracting is more beneficial than addition. In my own life, for example, I have benefited greatly by implementing a philosophy I call, Addition Through Subtraction (ATS).

ATS works by defining your three core values and twelve favorite questions. Then you use these values and questions as filters when deciding whether to add or subtract. This ensures you mostly add things of value to your life and remove things without.

The concept of Via Negativa doesn't only apply to your life. You can see it everywhere in modern society.

For example, the number of people given antibiotics has decreased substantially in the past few decades.

This is because using antibiotics on nonserious diseases runs the risk of creating super bacteria resistant to the antibiotic medicine we use. This is because using antibiotics on nonserious diseases can create super bacteria resistant to the antibiotics.

Another example is the Amish. They only add a technology to their lives if it aids one of their three main values: god, family, and community.

One of my favorite examples of beneficial subtraction, however, is in building wisdom. Most people mistakenly believe wisdom comes from ingraining more knowledge.

But as the Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu advised, "To attain knowledge add things every day. To attain wisdom subtract things every day." This philosophy is known as subtractive epistemology, the idea that wisdom comes primarily from subtracting what we know is wrong instead of adding more of what could be right.

🤙Skin in The Game

Finally, the last concept Taleb discusses in the book is skin in the game. Having skin in the game means you have something to lose from being wrong. In other words, you practice what you preach.

Never ask a doctor what you should do. Instead, give them skin in the game by asking what they would do in your position.

Having skin in the game is crucial because it keeps you accountable for spreading useful and true information. If there is no skin in the game, nothing except pure moral standards keeps people from half-assing or outright lying.

I have given myself skin in the game in this blog post. Throughout the post, I have given examples of how I have implemented the books concepts in my own life.

This gives me skin in the game. I have something to lose if these examples don't work because I practice them.

For instance, I don't preach about fasting while eating breakfast, lunch, and dinner with snacks. As of writing, I'm currently on a 34-hour fast after flying back home from Amsterdam the day before. I feel absolutely fantastic!

And it's not only from fasting. I'm living my best life by making myself antifragile. I transformed my fragile life system from two years ago into an antifragile one through preparing for Black Swans, implementing ATS, and giving myself skin in the game.

Now it's your turn.

Learn more about the concept of Antifragility by getting the book!

Make yourself Antifragile.

Thanks to Astrid Helfant for the conversations which helped form this blog post.